I don’t remember exactly when I picked up Christianity and the Crisis of Cultures — or why — but it was on my nightstand, unread, for many months until Brendan came home from UMary and mentioned it was one of the good books he read in his Catholic Studies classes this year. Essentially a lecture delivered by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (now Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI) circa 2005, the book highlights the ways in which Europe’s widespread Christianity served as a foundation for many of the great advances of the Renaissance and Enlightenment, which have paradoxically led to a severing of the Christian roots that made them possible and a grave imbalance between technology and morality, between what we can do and what we should. Yet even as we stand on the brink of cultural collapse, Cardinal Ratzinger proposes an approach that could restore the moral foundations of Western societies and lead people back to God.

I don’t remember exactly when I picked up Christianity and the Crisis of Cultures — or why — but it was on my nightstand, unread, for many months until Brendan came home from UMary and mentioned it was one of the good books he read in his Catholic Studies classes this year. Essentially a lecture delivered by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (now Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI) circa 2005, the book highlights the ways in which Europe’s widespread Christianity served as a foundation for many of the great advances of the Renaissance and Enlightenment, which have paradoxically led to a severing of the Christian roots that made them possible and a grave imbalance between technology and morality, between what we can do and what we should. Yet even as we stand on the brink of cultural collapse, Cardinal Ratzinger proposes an approach that could restore the moral foundations of Western societies and lead people back to God.

It is a short (115 pages of well-spaced text), but heady, read — unflinching yet hopeful in its outlook, recalling that all things are possible through Christ. Two major ideas touched on in the book stand out to me this morning, each of which I will paraphrase and tackle in somewhat of my own way so as not to spoil the lecture itself.

The first is that we live each day by faith, which is never blind but always rooted in authority of those who have firsthand knowledge of the subject at hand. An example a friend of mine shared some months ago: how many of us know our birth mother? How do we know? None of us can possibly recall the moment of our birth, and few if any of us have incontrovertible photographic evidence of that moment, with faces in focus and the umbilical tether uncut. We could have been adopted or inadvertently switched. But we have faith based on authority: the signed documents, the witness of family members and friends, and in most cases the presence and loving care of our mothers themselves.

Most of us aren’t engineers, yet we trust another’s deep understanding of engineering to get us to and from work safely each day and to perform our work functions. Most of us no longer raise the majority of our food, yet we trust that it is safe to eat. In the same way, while many of us do not claim to have firsthand knowledge of God in person, our faith is based on the authority of those who did (or do): signed documents, the witness of family members and friends, and the loving care of the Creator Himself.

Indeed, without this foundation of so-called irrational faith — this fundamental belief and trust in things outside our own personal experience — everything else, including the science and technology we cling to as “rational,” breaks down.

The second idea worth highlighting is that, as Cardinal Ratzinger puts it, “It is an obvious fact that the rational character of the universe cannot be explained rationally on the basis of something irrational!” If the origins of the universe, the world, and humanity are random, how then can we rely on them to unfold in a rational way and be understandable? If our brains are merely chemicals and electrical impulses particularly suited to our survival, what are reason and choice, and why do they matter?

Cardinal Ratzinger puts forth a compelling picture of the modern culture and offers advice for believers and non-believers alike to rebuild the crumbling foundations of Europe and the West. Brendan found this little book worthwhile, and so did I.

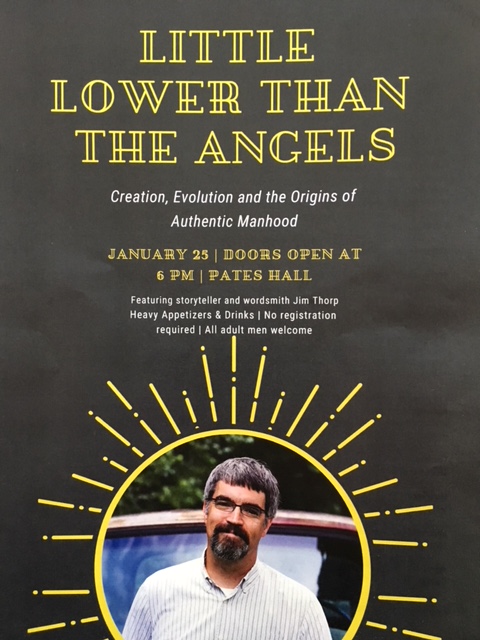

Late last month I was invited to speak to the Men’s Club at

Late last month I was invited to speak to the Men’s Club at  Being without work these past few weeks, I’ve had more time than usual to read. Last weekend, I finished Walter M. Miller’s 1959 novel A Canticle for Leibowitz, a book recommended to me by three of the smartest men I know. Set in post-apocalyptic America in the centuries following a nuclear holocaust, it tells the story of the monks of the Albertine Order of Leibowitz, who scratch their livelihood from the rocks and dust of the southwestern deserts and dedicate themselves to their founder’s mission of extracting knowledge from the rubble of the previous civilization and preserving it for the future.

Being without work these past few weeks, I’ve had more time than usual to read. Last weekend, I finished Walter M. Miller’s 1959 novel A Canticle for Leibowitz, a book recommended to me by three of the smartest men I know. Set in post-apocalyptic America in the centuries following a nuclear holocaust, it tells the story of the monks of the Albertine Order of Leibowitz, who scratch their livelihood from the rocks and dust of the southwestern deserts and dedicate themselves to their founder’s mission of extracting knowledge from the rubble of the previous civilization and preserving it for the future.  I don’t remember exactly when I picked up Christianity and the Crisis of Cultures — or why — but it was on my nightstand, unread, for many months until Brendan came home from

I don’t remember exactly when I picked up Christianity and the Crisis of Cultures — or why — but it was on my nightstand, unread, for many months until Brendan came home from