This cold winter night,

that old wooden-head buddha

would make a nice fire

– haiku by Buson

It’s cold this morning – the kind of cold that, after just a few minutes, makes you imagine what you’d do to stay warm if you didn’t have a warm house close by …

The haiku by Buson illustrates this feeling nicely, I think, with subtle humor. It is detailed and concise – saying just enough to capture your attention and spark your imagination. You can read it and “get it” immediately – or you can think on it and uncover some deeper truth about the world. It conveys the poet’s mindset and message, not by taking the reader by the hand, but by setting the reader’s mind on the path and trusting they will arrive in due time. In my ongoing discussions with Cowboy Bob regarding what makes a poem a poem (especially poems that don’t have clear rhythm or rhyme) this is perhaps the best explanation I’ve found.

People wonder sometimes why I’m fascinated with Asian poetry and film. It is in part because, in many cases, the Asian masters seem to have perfected something many Americans (especially film-makers) seem to have lost – the Art of Understatement. (There are notable exceptions, of course, including classic kung-fu and samurai flicks, which appeal to me for entirely other reasons. More on that another time.)

*****

Wrapping dumplings in

bamboo leaves, with one finger

she tidies her hair

– haiku by Basho

Film critic Roger Ebert says, “If you have to ask what something symbolizes, it doesn’t.” He makes a good point – symbols cannot be so obscure that no one grasps them. But scenes, references and language that make you think – or better still, feel – without telling you how or why offer opportunities for discovery.

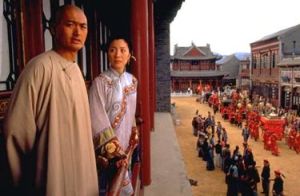

Consider two of my favorite “love scenes” on film, one from an Asian filmmaker (who has made “American” films) and the other from an American filmmaker, but in a film set in imperial Japan. In Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon is a scene in which Chow Yun Fat and Michelle Yeoh – two star-crossed warriors who’ve loved each other for years but have been unable to act upon that love – enjoy a quiet moment and a cup of tea. He takes her hand and brings it to his cheek, and you can feel their ache for each other. They exchange a few simple lines, as I recall, but that’s it. Their faces and hands tell the story. (If anyone knows where to find this clip online, let me know. You can see a portion of the scene as part of this montage from the film, near the 2:15 mark – thanks, Tyler!)

There is another love scene in the movie that is more aggressive (and more biomechanically accurate), but even this scene is short and and involves no nudity – and yet you have no doubt what has happened, both physically and emotionally.

And in Edward Zwick’s The Last Samurai, Tom Cruise’s character, who has been cared for by the widow of a samurai he killed (she does so on orders from her brother, the leader of the clan) is dressed for battle by her in her late husband’s armor. The woman has come to love him, and although they do kiss (once, and lightly), they wouldn’t have to for the scene to be effective. No nudity. No slo-mo. No sweat.

Now, I know that Asian films and filmmakers aren’t always this subtle – Ang Lee, in particular, has pushed the envelope with his portrayals of sexuality, both in the States and abroad. But what catches my attention is 1) how relatively rare it seems that an American film takes the more subtle route, especially in terms of love or sexuality (and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Zwick’s scene is in a movie set in the Far East), and 2) how this subtle approach parallels, in my mind, haiku and other Asian poetry.

Maybe it’s what I’ve come to expect, or the movies I choose to see – or maybe Asian film-makers are exporting what they think Western audiences want from them. Whatever the case, it’s clear to me that these movies approach their subject matter from a different mindset, and that mindset intrigues me.

*****

Both of these movies, and other similar films, also end on a note of uncertainty. The American film tries to tidy up a bit at the end – gives you one possible outcome – but neither is altogether happy or altogether neat. My wife hates that …

One last haiku – perhaps the best I’ve found at taking the reader to the verge and then letting go:

This world of dew

is only a world of dew –

and yet

– haiku by Issa

Blogger’s Note: Top two photos of Chow Yun-Fat and Michelle Yeoh in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. (© 2000 Sony Pictures Classics. All rights reserved.) Bottom photo of Tom Cruise and Koyuki in The Last Samurai. (© 2003 Warner Bros. All rights reserved.)

I'm with Jodie on this one. 😉

Good post. Worth the wait, but did it have to be that long of a wait?!

LikeLike

Actually, yeah, it did. I'm writing other stuff, too! It takes as long as it takes!

Glad you keep checking back, though …

LikeLike

Thanks Bob, at least I have someone that agrees with me. Give me a romantic comedy!

LikeLike

There are moments romance and comedy in both of these movies, just like in life! Show me a life with a neat, happy ending and no suffering, and I'll film it myself! 🙂

Yeah, I tend to like the darker comedies. And Romeo and Juliet — romantic tragedies. Sorry, hun.

LikeLike

Try the following link for a clip:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GFJYrXzaLlo

(Starts at 2:15)

Maybe that's what you're looking for.

****

The problem with certain poetry and literature (by my estimation) is that it tells you too precisely what to think. Tolstoy argued that the value of a piece or art could be known by its capacity to make the recipient fell that which the artist felt. I tend to agree with Tolstoy. What seems implicit in this thought, though, is the fact that language is too imprecise to communicate a feeling. Thus, poetry, prose, and other forms of literature have to allow language to do something more than we are used to permitting. Typically a single word communicates a single idea, and represents a thing which exists outside of the subject, or at least, something common to people – something to which everyone can have access. For instance, when I say chair, we all know that this combination of letters (or sounds in our spoken language) is not itself a chair, but represents a thing that exists in our homes upon which we sit. Likewise, when i use the word angry, we all understand the emotion that this word symbolizes. However, when one hopes to really communicate oneself, simple words do not suffice, and the multiplication of words only serves to confuse the issue further. It seems better to allow the poet to express himself and then hope that the words stir some resonance within the reader. Too many words, too much (attempted) precision prevents one from having access to the soul of the author because the emotion itself is too foreign to the reader.

LikeLike

Tyler,

That's it, and that's it!

The scene is cut short for this montage — but hey, you get a feel for an otherwise beautful movie, too. Just wish they would've let Yo-Yo Ma's cello carry the musical weight.

And your analysis is exactly what I'm thinking. To me, the poet's art, in particular, is to convey an occurrence — an event, a scene, a feeling — and a deeper significance beneath it, something universal that everyone can relate to, even if they've not experienced the occurrence.

If that's true, then:

A) it explains a bit why people claim not to “get” poetry — because they recognize (either in reading it or from the fact that someone called it “poetry”) that there's something more to it, and so they start looking for Symbols and Meaning,

and …

B) it takes the pressure off regarding “getting” it — you take from it what you're ready to take, if you put the time in.

That's what I love about haiku — they push the writer to be concise, and they tend to describe very simple, natural, sometimes mundane, scenes. We can admire them for the tiny glimpse of life they show, or we can look underneath for something more.

I may mess around with a couple of haiku this week, just to see how this notion plays out. Maybe in another post …

LikeLike

Okay, now I think I might have a glimpse of what you are saying!

Thanks guys!

LikeLike